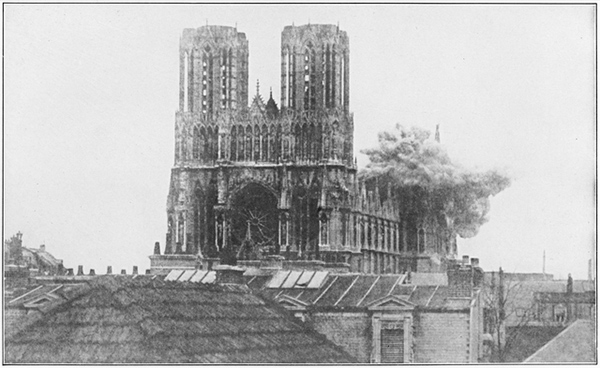

A shell bursts on the cathedral of Reims during World War I. Unknown photographer in Collier’s New Photographic History of the World’s War (1919), page 86

A small section in the Getty Research Institute’s exhibition World War I: War of Images, Images of War commemorates an event that provoked one of the most intense and vociferous international press campaigns of the period: the shelling of the cathedral of Reims by German troops in September 1914.

What exactly happened can probably never be reconstructed in full detail. German canons struck a world monument, a deplorable and inexcusable incident after which the war took a catastrophic and acrimonious turn. Following a brutal military campaign that began with the invasion of neutral Belgium, the German army proceeded to France and moved into the city of Reims, but had to retreat when the French army reentered the city. After the first shelling on September 4, 1914, the city was bombarded by the German army more heavily on the 18th and 19th. In the course of these attacks, the cathedral took fire. The wooden roof burned, statues were mutilated, and the precious glass windows were destroyed.

The general view expressed by the French commentators at the time was that the shelling had finally revealed the real character not only of the military leaders of Germany and the commander in chief, Kaiser Wilhelm II, but of the German people in general. Many French authors wrote that the Germans had not only declared war for political reasons, but to destroy French culture. The bombing was accordingly reported as a deliberate act of vandalism. Observers argued that the Germans had specifically intended to destroy the cathedral—a sacred national monument. A new and extremely aggressive tone in French propaganda and intellectual debate arose, in which the Germans were denounced as Barbarians, Vandals, and Huns.

The counter-propaganda on the German side did not sleep either: the German press portrayed commentators from Belgium, France, and other countries as liars who intentionally falsified reports about the events. In the case of the Reims shelling, the German press especially discussed military reports according to which the French had concentrated troops in front of the cathedral and used its towers as observation points to monitor the movements of the German troops.

German propaganda card from 1917. The text reads, “The French use the cathedral of Reims as a base of operations and therewith endanger this magnificent work of art” (“Die Franzosen benutzen die Kathedrale von Reims also Operations-Baßis und gefährden damit das herrliche Kunstwerk”). via reims.fr

This bitter controversy could be dismissed as a typical wartime propaganda dispute. However, we have to investigate deeper strands to understand the magnitude of the confrontation provoked by the shelling of Reims cathedral. The event profoundly shocked French intellectuals, who for the most part had held an intense admiration for German literature, music, and art. By relying on press accounts and abstracting from the visual propagandistic content, they were unable to interpret the siege of Reims without turning away from German culture in disgust.

Similarly, the German intelligentsia and bourgeoisie were also shocked to find themselves described as vandals and barbarians. Ninety-three writers, scientists, university professors, and artists signed a protest directed against the French insults that defended the actions of the German army.

The fight of words and images ignited by the Reims attack continued throughout the entire war, stressing the differences between German Kultur and French civilization. Stereotypes with roots deep in the past became the prevalent motifs of this acrimonious controversy.

Destroy this Mad Brute—Enlist, ca. 1917, Harry R. Hopps (American, 1869–1937). Color lithograph. The Louis and Jodi Atkin Family Collection, Modern Graphic History Library, Washington University Libraries

The shelling of Reims cathedral is a fascinating historical moment, one that helps us understand the coming conflagration of World War I. Intellectuals on both sides were not able to avert blind and brutal military actions. They failed in France, as in Germany, to create a climate of reason and responsibility. Far from being impartial and independent, they, like many others, donned blinders and followed the reigning political propaganda. They identified not with patriotic feelings, but rather with nationalistic ones, nurturing illusions of military and cultural superiority.

One positive development, however, did emerge from this event: The German government installed the so-called Kunstschutz (bureau for the protection of monuments). This military department was created to counter the huge international protests that erupted after the burning of the library of Louvain in Belgium and the cathedral of Reims in France. The Germans sought to answer their accusers by demonstrating that Germany respected and protected cultural monuments in countries it had invaded. They could even refer to the fact that the Kunstschutz was run by professionals—art historians and architects.

No other country participating in the war had a similar institution. It would, however, later become a model for other initiatives, such as the famous Monuments Men, a group of art experts who were commissioned by the U.S. Army during World War II to rescue as much of European culture as possible.

_______

Hear Thomas W. Gaehtgens, director of the Getty Research Institute, speak about the bombing of Reims in a free lecture on March 19, 2015. The series begins on January 25 with a discussion of the Austrian avant-garde by Marjorie Perloff, and continues on February 22nd with an exploration of wartime trauma by Gordon Hughes and Paul Lerner. Learn more and RSVP here.

Comments on this post are now closed.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks